Darjeeling Himalayan Railway: The little blue train

Darjeeling Himalayan Railway: The little blue train

According to an 1896 publication, Illustrated Guide for Tourists to The Darjeeling Himalayan Railway and Darjeeling, the Darjeeling Mail Train would leave Calcutta at 4.00 pm. Dinner would be served on the steam ferry crossing the Ganges, the guide recommends the Hilsa fish curry, finally arriving at Siliguri at 8.23 am. Breakfast would be served in the station restaurant before transferring to the little blue narrow gauge train for the final leg up to Darjeeling.

These days the Mail train leaves at 10.00 pm, crosses the Ganges by bridge at Farakka and dinner is served in aluminium containers. Or you can fly from Calcutta, now known as Kolkata, to Bagdogra airport, which is about six kilometres from Siliguri, in a little less than an hour. From there a jeep will whisk you up to Darjeeling in around 4 hours. Since flights leave Kolkata early in the morning it is possible to be on the Chowrasta in time for a late lunch or afternoon tea. But where is the adventure in that?

There is little to see on an overnight train journey so you might as well fly. But the little blue train, affectionately known as the Toy Train, still trundles up the hill. Mark Twain, writing in his journal in 1896 wrote; “The railway journey up the mountain is forty miles, and it takes eight hours to make it. It is so wild and interesting and exciting and enchanting that it ought to take a week.”

There is only one train a day that covers the whole distance and these days it starts at New Jalpaiguri, an extension that was added in the 1960s when Indian railways were going through a period of modernisation. According to the timetable, 08.30* is the departure time but that only guarantees that it won’t leave before then.

My train didn’t even pull its empty coaches into the station until 09.10 and finally got underway some twenty minutes later. From there on it drifted further and further behind schedule and it seemed almost as if Indian Railways were taking the famous author’s advice. Nobody seemed to mind, the local passengers knew only too well what to expect, we visitors were enraptured as the scenes changed and unfolded beyond our windows.

The locomotive is a stocky rectangular block of raw power, slightly wider and taller at one end for the cab. The coaches seat about twenty-four with doors at only one end but boasting large windows through which to enjoy the views. Finally, underway, the first section shadows the main line as it skirts around the chaos and infernal traffic of the town to Siliguri Junction.

The British East India Company had established Darjeeling as a sanatorium back in 1835. A place with a more agreeable climate where sick and weary company officials could escape the oppressive heat and humidity of Calcutta to recuperate. But even as late as the early 1870s the journey from Calcutta to Darjeeling was a grueling one. It involved taking a train from Howrah station to Sahibganj, crossing the Ganges by steamship and proceeding from the other side by two-wheeled bullock cart up the Pankhabari Road to Kurseong and then on to Darjeeling. The trip would take about six days and anyone embarking on it, even in rude health, would no doubt be feeling sick and weary by the end of it.

A rail link from Calcutta to Siliguri opened in 1871 which was followed ten years later by the opening of the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway cutting the journey time to just 24 hours.

Siliguri

There is little of interest in Siliguri itself though the station does have a series of panels offering interesting morsels of information about the various stops along the way. The old locomotive shed is a short walk up the line but it is deserted save for two cold and lifeless 0-4-0 tanks built, like all of the railway’s steam locos, by Sharp, Stewart and Company of Glasgow between between 1889 and 1925.

There had, at some point in the past, been steam-hauled Joy Ride services from here to Sukna where tourists could visit the Mahananda Wildlife Sanctuary. Here, if you are lucky (or not, depending on your circumstance), you might encounter tigers and elephants as well as a wide variety of bird species.

Leaving Siliguri, the line joins the Hill Cart Road which it will flank all the way to Darjeeling. Here the road is busy with trucks and trishaws, groups of schoolchildren in crisp uniforms and gardens bright with pink bougainvillea, rhododendrons, and marigolds.

Waiting at Tindharia station for the train travelling in the opposite direction to pass (left). Kurseong Station (right)

After Sukna the climb begins in earnest. There is forest on both sides of the line now, and the eagle-eyed will be able to spot orchids and bromeliads amongst the trees. As the road begins to twist and turn the train, favouring gentler bends, crisscrosses the road. There are no traffic lights or level crossing gates but the train makes plenty of noise and always has the right of way.

The railway up to Darjeeling had first been proposed by Franklin Prestage, an agent of the East Bengal Railway, who had seen the growing need for a more efficient way for the area’s burgeoning tea industry to get its produce to port, as well as getting products back up the hill to the rapidly growing populations of the towns and villages along the route. Getting approval had been the easy part, building it presented a whole new set of challenges.

Read also: War, subterfuge and a nice cup of tea Read also: The North Borneo Railway: Steaming Back in Time

It is 62 kilometres from Siliguri to Darjeeling and in that short distance the train has to follow a winding path which starts at 122 metres above sea level at Siliguri climbing to 2,257 metres at the little town of Ghum, the highest point on the line about 6 kilometres from Darjeeling.

Narrow gauge was the only option but even that couldn’t cope with the tightness of the bends or the more extreme gradients. A road can wind its way up a steep hillside a railway has to employ other methods. The first of these is a zig-zag. The train moves upwards onto a spur, then reverses to a second spur above the part of the line that it just passed over. It then moves forward and upward again increasing altitude within a comparatively short distance.

After three of these zig-zags, we pause at Tindharia. The air is already appreciably cooler so piping hot chai and samosas are ordered. The line is single track all the way so we must wait for the train to pass in the opposite direction.

Agony Point and Kurseong

Another device for gaining altitude is a loop where the line coils upwards and over itself. The first of these is called Agony Point and is just beyond Tindharia. There are four of these on the line but this is the tightest, with a diameter of just 18.2 metres. As we inch our way around the train creaks and the wheels screech, a reminder of just why it is called Agony Point.

From here we are rewarded, both left and right, with views of small villages perched on hilltops and breathtaking panoramas across the surrounding valleys swathed in the waist-high bushes of one of the world’s most famous teas. Indeed a stopover at the next town, Kurseong, is a must for any tea connoisseur. Kurseong is the home of both Makaibari and Castleton two of the oldest and most famous tea gardens in the region. Visits can be arranged to both factories and there are numerous friendly homestays in the area.

Ghum is the highest station on the line

Kurseong also has the dubious reputation of being one of the most haunted towns in India. The locals I spoke to said it was a silly idea perpetuated by schoolboys. Nevertheless, a stroll up to the two old schools and the little chapel through the frequently mist-shrouded woods on Dowhill, above the town, does reveal plenty for fertile imaginations to conjure with.

Leaving Kurseong, the Chatakpur forest rises to the right and Margaret’s Hope Tea Garden tumbles down the hillsides to the left providing stunning views all the way back to the plains around Siliguri and Bagdogra.

Ghum to Darjeeling

The final stop before Darjeeling is the busy little town of Ghum. At 2,257 metres Ghum is the highest point on the line. It boasts a small but interesting railway museum with old locomotives, rolling stock and photographs. There are also some old and interesting monasteries nearby.

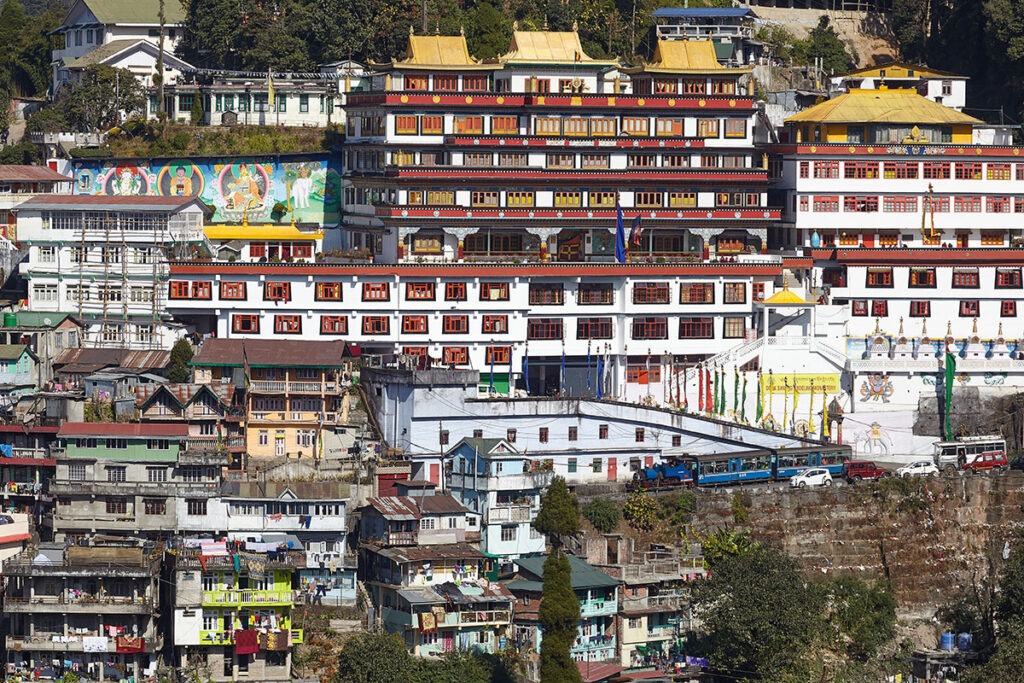

While there are glimpses earlier Batasia offers the first panoramic views of Mt Kanchenjunga. At 8,586 metres it is the world’s third highest mountain. Surrounding it, the jaw-dropping majesty of the Himalayas which forms the backdrop as the town of Darjeeling spills down the hillside. The mountains will be visible for most of the rest of the way but it is worth keeping an eye open for the large and colourful Dali Monastery, also known as the Druk Thupten Sangag Choeling Monastery.

Over and under at the Batasia Loop (above). Passing the Druk Thupten Sangag Choeling Monastery on the way to Darjeeling (below)

The last stretch of road into Darjeeling is very busy but before long the train rumbles past the locomotive shed, where a few hundred-year-old steam locomotives will be softly hissing, and into the little Art Deco station.

Daily steam and diesel joyrides operate between Darjeeling and Ghum. Tickets can be booked at Darjeeling station. It is also possible to charter steam-hauled services for large groups.

The best times to visit Darjeeling are Spring through to early Summer when temperatures are a balmy 20-23ºC. Late Autumn when temperatures are much lower at around 8-15ºC but visibility is at its best.

*The timetable has since been updated and the train is now scheduled to depart at 10.00 am. It is scheduled to depart from Kurseong should be at 14.45. Travellers should, however, check for the latest schedule at the station.

Places to stay in Darjeeling

Windamere Hotel Central Gleneagles Heritage Resort Mayfair Hill Resort