The sweet smell of steam: A century old sugar mill in East Java

The sweet smell of steam

With a shrill whistle, a cloud of thick black smoke and much clanking of steel engine No4, Semeru, with its one truck load of passengers chuffed through the gates of the Olean Sugar Mill and onto the street. The guard waved a red flag to stop the traffic as it crossed the road but, at the sound of the whistle, the traffic had stopped anyway. Children waved and drivers got out to watch as we shuddered along the road. This train wasn’t built for comfort, it had been built to haul sugar cane from the fields back to the mill for processing.

Sugar has long been cultivated in Java. As far back as the fifth century Chinese travellers had mentioned the manufacture of gur, cakes of unrefined sugar, from cane and palm juice in their chronicles. The large-scale processing of sugar was adopted by Chinese immigrants early in the fifteenth century who had built up wealthy trading networks.

In 1619 the VOC (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie or Dutch East India Company) muscled in and monopolised the trade. The sugar was still produced by the Chinese but they were forced to deliver it to the company at fixed rates. The VOC was dissolved in 1798 but the fall of the Netherlands to France in 1806 saw five years of French administration, followed by four British before being handed back to the Dutch in 1815. It wasn’t until 1830 that the Netherlandsche Handelsmatschappij (NHM), a new trading monopoly that had been established in 1824, put in place a new system whereby planters were paid a fixed wage but were forced to grow only crops such as sugar, tobacco, coffee and pepper. Almost all of these crops were exported.

Demand for sugar was increasing dramatically in the West. During the mid and late nineteenth century, diets had been changing to include jams and candies and other sweet victuals which hadn’t existed before. Sugar was used as a sweetener for tea, coffee and cocoa. Britain alone was consuming five times more sugar in 1770 than it had been just 60 years earlier. As a result, sugar production increased dramatically. In 1830 sugar represented just 12% of the value of total exports with around 30 factories producing 6,467 tons. By 1896 this had jumped to 36% of the value of total exports with 187 factories producing 534,390 tons of sugar.

One of the key factors enabling this jump was the mechanisation of agriculture and sugar production was leading the way. From early in the nineteenth century water mills had been steadily replacing animal power and these, by the middle of the century, were being replaced by steam engines. The first centrifuges for the efficient separation of sugar and syrup were imported in 1853.

But it was the Sugar Act of 1870 that changed the game completely. The compulsory surrender of land and labour came to an end. As a consequence sugar factories had fields of cane which needed harvesting and processing therefore factory mechanisation was imperative for survival. The Dutch had been late industrialisers and were not equipped to supply the mills with all the steam-based technology they required. This led the mills to become reliant on British, French and German engineering. The only part of the process that remained unmechanised, and remains so to this day, is the harvesting of the cane itself.

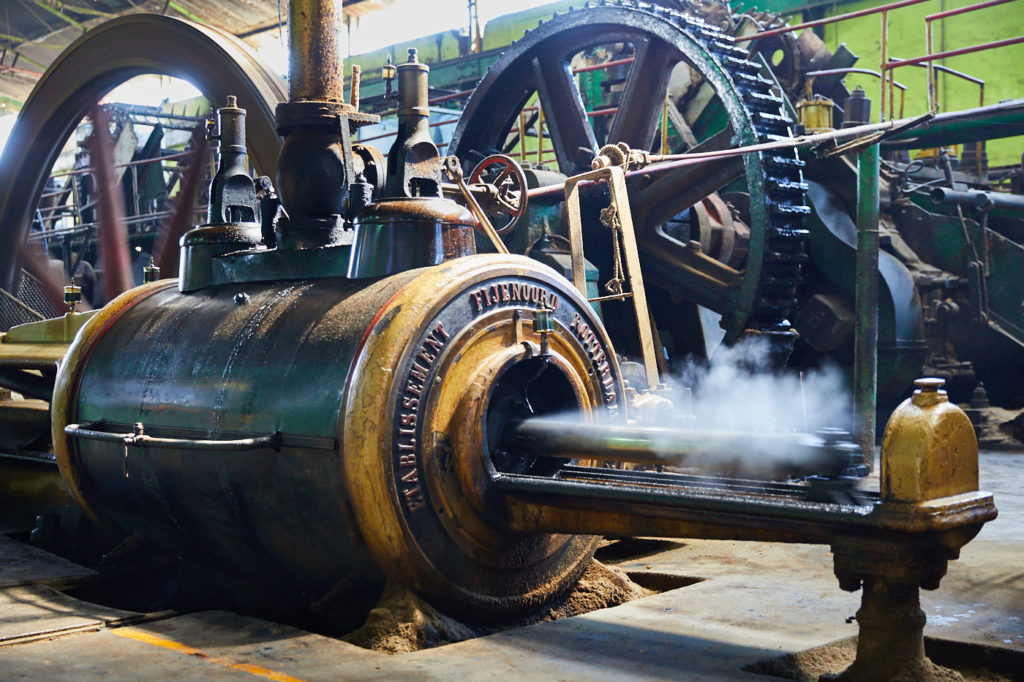

At Olean cane is brought to the mill by both road and rail though, for the latter, day-to-day operations are all diesel hauled. But once inside the factory the atmosphere is much the same as it was a century ago. The mill started operations back in 1841 and the buildings, classic Dutch colonial style, haven’t changed since. The first thing to hit you when you step inside is the noise, the rhythm of huge con-rods and flywheels that drive the crushers. There are pipes going in all directions, pistons and pressure gauges, cogs, levers and belt drives. It’s possible to see machinery such as this in various museums around the world but there it is cold and lifeless. Here it is alive, here it is breathing. An intoxicating mix of steam, sugar and oil.

After the cane is delivered from the fields it goes into a crusher. This breaks the cells in the stems so that the juice can be extracted. From there it passes on to the first of two mills where the juice is squeezed. After the second mill hot water is added and then passed through the mill again to maximise the sugar recovery.

Once the juice has been extracted it is heated and lime is added to help remove impurities. This alters the pH balance of the sugar which must then be neutralised with a sulphur dioxide gas. After this, the juice is heated again to evaporate some of the water and then passed through a series of vacuum filters. More water is then boiled off until crystals start to form. This mixture of thickened juice, or syrup, is called massecuite. From here the massecuite moves to the crystalliser where it cools and the crystals continue to develop.

When the crystals are ready they are spun in centrifuges to separate the crystals from the syrup washed and dried with hot air ready for bagging. On a typical day, the mill will process about 1,000 tonnes of cane producing about 60 tons of sugar.

One of the reasons that Olean can still operate steam machinery in this day and age is that its primary fuel is bagasse, the cane residue that is left after the crushing process is complete, a by-product of the process. Bagasse is used to stoke the fires that heat boilers which in turn keep the machinery running. But keeping the machinery in good running order is another question.

Semeru is the only surviving steam locomotive out of four that were originally supplied by Orenstein and Koppel of Berlin almost a century ago. The others, having fallen into disrepair were probably scavenged for spare parts in order to keep the one in good working order. But it is an issue that affects not only the locomotive number 4.

With a factory full of machinery that, in some cases, is over a hundred years old maintenance is a serious challenge. There is no documentation and no spare parts. Indeed most of the companies that built it no longer exist, nor do the necessary skills. When a part needs replacing, a part which might weigh several tons, the plant has to make its own. Thus the engineering and mechanical skills to perform such tasks have to be passed on from one generation to the next via on-the-job training. From blacksmiths to bricklayers, riveters, fitters and firemen and the tools with which they ply their trade, all are alive and well in the company’s workshops.

The fire carts of Xishi: An old mining railway deep in the heart of Sichuan

For many years the existence of Olean, and other mills like it, has been known only to a small number of enthusiasts who shared videos and information online. Other mills still have some steam machinery, and one or two still have working steam locomotives which they will fire up for visitors. Olean is the only mill left that is still processing sugar with a complete set of vintage machinery. Despite the pressure to modernise the company’s management is keen to take a different approach. They want to keep things exactly as they are and market themselves as a heritage site.

Semeru trundles along the side of the road for a hundred metres or so then the track bares left past a small copse of mango trees before breaking out into emerald green fields of young sugar cane under a cloudless blue sky. To the west, the outline of Gunung Argopuro sits hazy on the horizon. After a while we stop for a photo-op. People that live in the area see the diesels regularly during harvest time, nobody pays them any mind. But when a steamer shows up so do all the children from the village. These kids have probably never heard of Thomas the Tank Engine but somehow the steam train still captures both their imaginations and their hearts.